The Cheese Lady, located in the Downtown Farmington Center, stands on hallowed ground—in the cheese-making realm, at least.

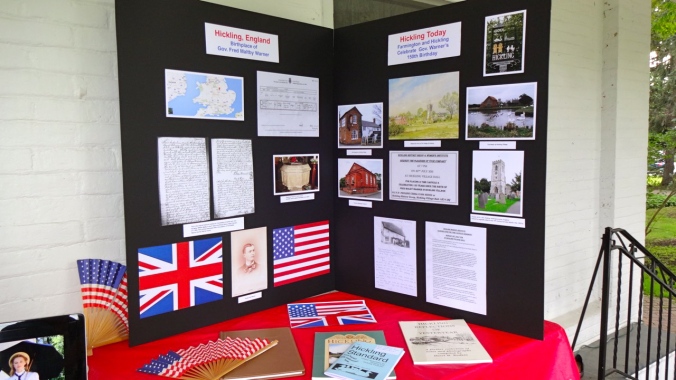

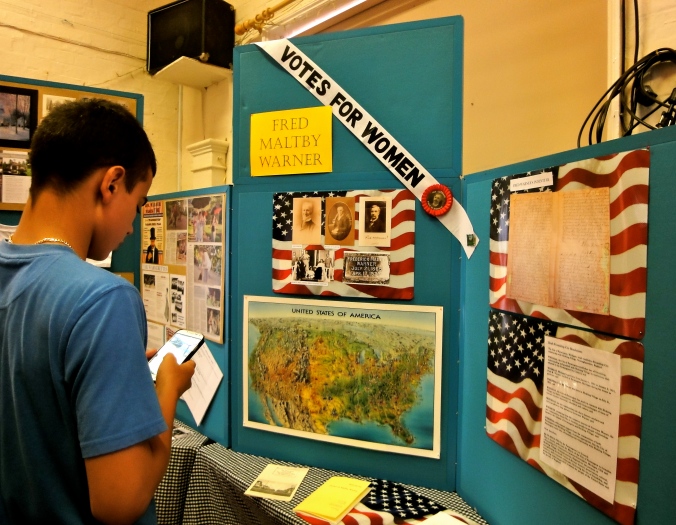

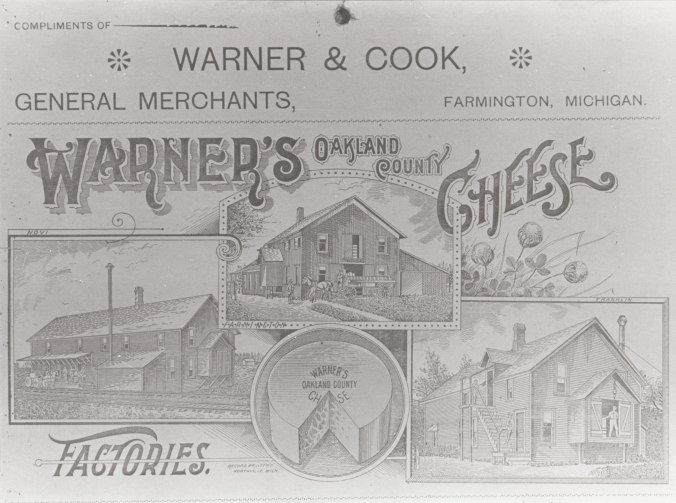

Farmington has a legacy of cheese. It started in 1889, when local resident Fred Warner opened a cheese factory on the site of what is now the Sundquist Pavilion. Later, he would go on to become governor of Michigan.

And in Farmington, his factory would kick off a niche empire that dubbed Warner the “Big Cheese” of Michigan.

SETTING UP SHOP

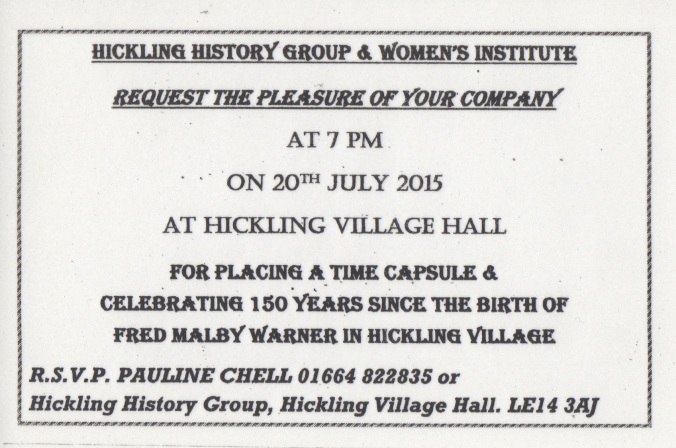

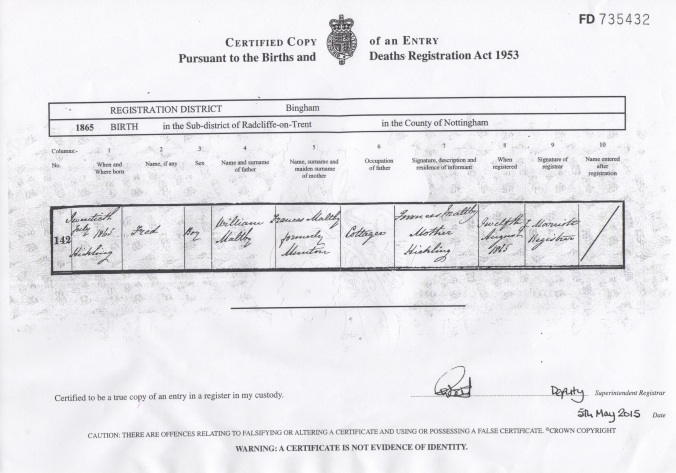

Cheese was in Fred Warner’s blood. Although raised in Farmington, Fred was adopted. His birthplace was Hickling, Nottinghamshire, an English dairy-farming community famous for Stilton Blue Cheese.

Warner started his cheese-making venture at the age of 22. “I was fortunate in getting a fine cheese-maker from Canada,” Warner told the Detroit Free Press in August 1906. After he had the machine, he went out to drum up business. “It was tough work,” he recalled. “Really, in the first two years I worked harder to get started than in all my life since. Prices were close, competition sharp. Had I not been lucky enough to get a good cheesemaker, I would have failed.”

Either way, a cheese factory wasn’t terribly expensive.

Warner’s, with an upstairs room for the cheese-maker, cost $2,500. “It was a wooden building down a lane—across from where the Methodist Church is now located,” remembered Murray Moore, who lived across the street from the Warner family from the 1890s to 1986.

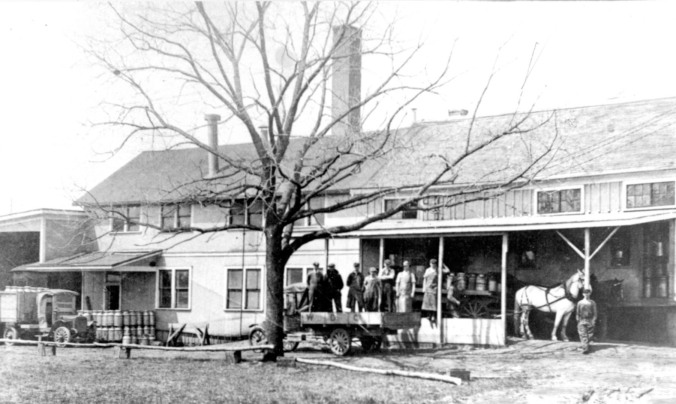

Milk was supplied by local farmers, who either brought it into town or sent it via pickup wagon.

KING OF CHEESE

In its first year, the Fred M. Warner Cheese Company produced 80,000 pounds of cheese. Within a decade, it had become Farmington’s most prominent industry.

Local success wasn’t enough. In 1894, Warner opened a Novi factory, near Grand River and Novi Road. The next year, he opened one in Franklin. Often, Warner bought out his competitors; in 1901, muckraking reporters at the Detroit Tribune printed rumors of a cheese monopoly. Warner’s 13th and final factory, in Livonia, came in March 1907. By this time, total output had reached 1.5 million pounds of cheese a year.

Most of Warner’s cheese was sold in Michigan. Customer records showed 48 distributors in Wayne County, 38 in Oakland County, and 24 in Ingham County.

There were outlets in the Thumb area, on the west side of the state, and as far north as Oscoda.

Cheese was sold at the downtown Farmington factory, too. “Good cheese always on cut,” Warner advertised in the Farmington Enterprise in 1904.

Apparently, the factory also gave free samples—making it popular with local kids. “Warner’s Cheese Factory…was a good place to stop when hungry,” reminisced Harley Waters in Farmington, Michigan in the Early 1900s. “Nate Eisenlord [probably an employee] would give his young visitors a handful of curd to get rid of them—or possibly because he liked them.”

Warner cheese must have been tasty. It won first place awards from the Michigan Dairymen’s Association, took prizes at the Michigan State Fair, and earned a gold medal at Michigan Agricultural College. “Fred M. Warner stands without a peer in the state as the best cheese man,” the Oxford Leader wrote in 1901. “He has built up his reputation by putting into the market the best quality of goods that could be made.”

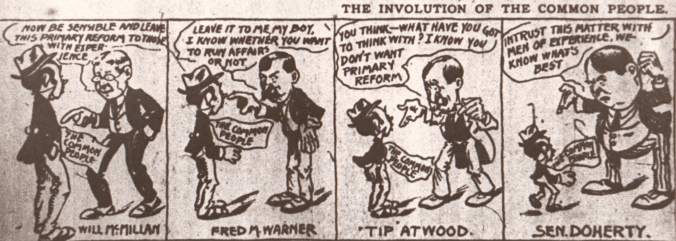

CHEESEY POLITICS

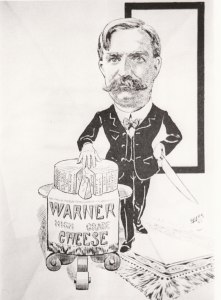

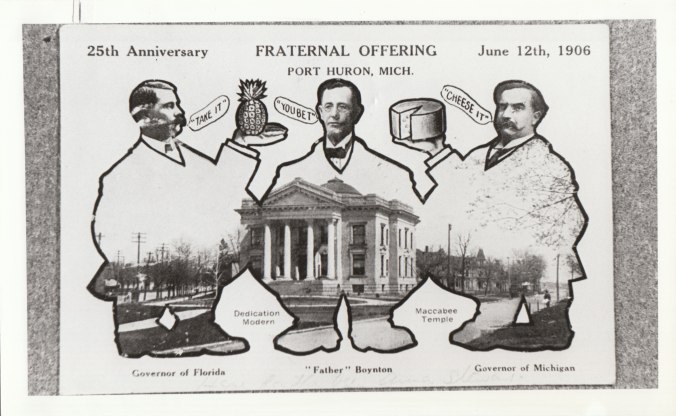

When Warner entered the political sphere, he didn’t hesitate to combine his product and his politics.

He served cheese and crackers at rallies and speeches, and he often featured large cheeses at State Capitol receptions.

Political cartoonists had a field day. “Warner is the Big Cheese,” ran one caption. (“Big cheese” was slang for an important person, or someone with a lot of money—a fitting nickname for a prosperous cheese-maker.)

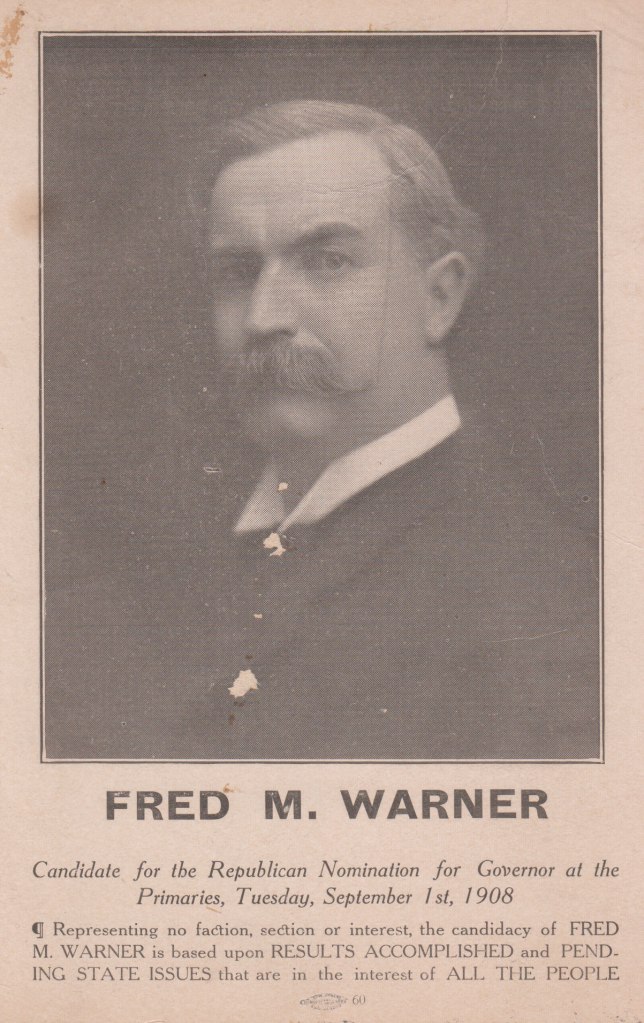

All joking aside, Warner’s business contacts served him well when he was mentioned as a candidate for governor. Farmers and businessmen alike knew him by name and by reputation.

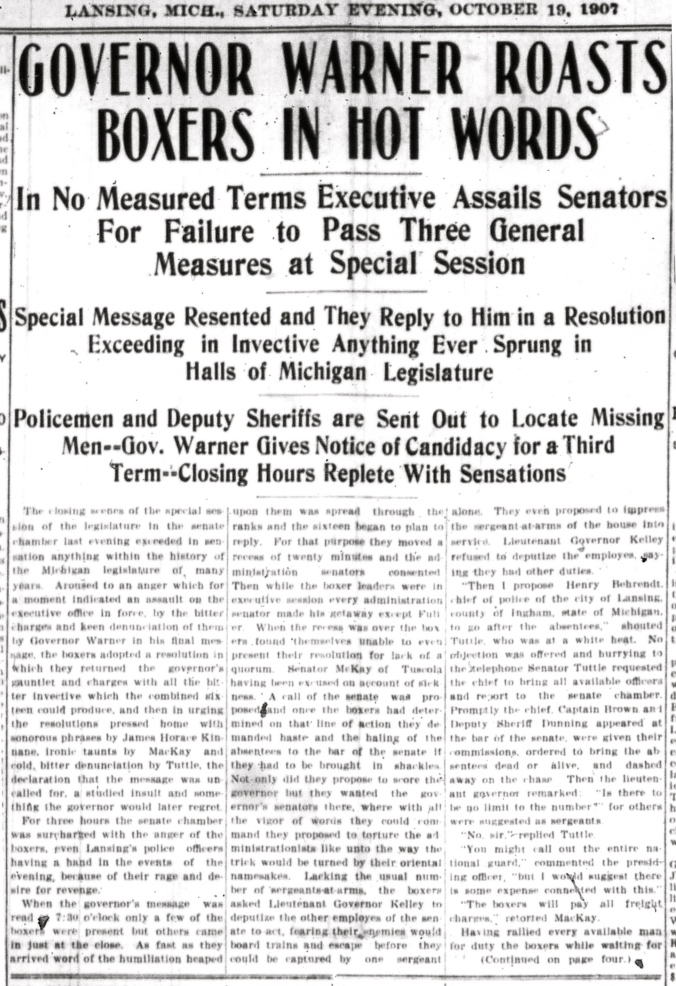

Warner served as governor from 1905-1911. In 1915, Warner’s venture was renamed the Warner Dairy Company, and started selling Cloverland Farm milk.

The Detroit Urban Railway built a spur track directly to the Farmington factory and outfitted a refrigerator car for shipping—the “only car of its kind in the country,” according to the April 16, 1915 Enterprise.

After Warner’s death in 1923, the company was run by his sons, Howard and Harley. It was dissolved in 1925.

Farmington Deputy City Clerk Sue Preuss (at left) watches while Andrea Fields (Detroit), Pam Becker (St. Clair), and JoAnne McShane (Farmington) enter the silent auction.

Farmington Deputy City Clerk Sue Preuss (at left) watches while Andrea Fields (Detroit), Pam Becker (St. Clair), and JoAnne McShane (Farmington) enter the silent auction. Toni Dombrowski (Macomb Township) contemplates the silent auction prizes.

Toni Dombrowski (Macomb Township) contemplates the silent auction prizes. Jennifer Edwards (West Bloomfield) and Cathy Lassiter (Bloomfield Hills) watch the raffle prizes being drawn during lunch.

Jennifer Edwards (West Bloomfield) and Cathy Lassiter (Bloomfield Hills) watch the raffle prizes being drawn during lunch. Tracy Freeman (Farmington) models the Mr. Song hat that she won in the raffle.

Tracy Freeman (Farmington) models the Mr. Song hat that she won in the raffle. From left to right: Judy Barrett (Farmington Hills), Louise Doute (Taylor), and Verna Paul-Brown (Taylor) hold hands during the “Ring of Friendship” greeting.

From left to right: Judy Barrett (Farmington Hills), Louise Doute (Taylor), and Verna Paul-Brown (Taylor) hold hands during the “Ring of Friendship” greeting. Music for the tea was provided by Warner Mansion pianist Annika Taylor, a Farmington resident and history student at Madonna University.

Music for the tea was provided by Warner Mansion pianist Annika Taylor, a Farmington resident and history student at Madonna University. Dessert: A chocolate-covered bombe cake served with berries, whipping cream, and a drizzle of raspberry sauce.

Dessert: A chocolate-covered bombe cake served with berries, whipping cream, and a drizzle of raspberry sauce. Linda Pudlik (at right) prepares to auction off the event’s top prize: Tea for six in the dining room of the historic 1867 Governor Warner Mansion, catered by Kelly Guarano of Kelly’s Cucina (at left).

Linda Pudlik (at right) prepares to auction off the event’s top prize: Tea for six in the dining room of the historic 1867 Governor Warner Mansion, catered by Kelly Guarano of Kelly’s Cucina (at left). Sherrie Stewart and Brian Golden of the Farmington Historical Society attended the tea in festive attire.

Sherrie Stewart and Brian Golden of the Farmington Historical Society attended the tea in festive attire.

![Michigan and its resources. ... Compiled under authority of the State by Frederick Morley. ... Second edition. [With a map.]](https://warnermansionmusings.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/11155232113_41bff49ea7_o1.jpg?w=676&h=409)